Is this really a breakthrough?

There is not yet a document which provides the specifics of an agreement, but the headlines are that the US will not be introducing any new tariffs this month and will halve those already in place in exchange for supposed commitments from China to increase imports from the US by $200 billion over the next two years.

But how credible is this?

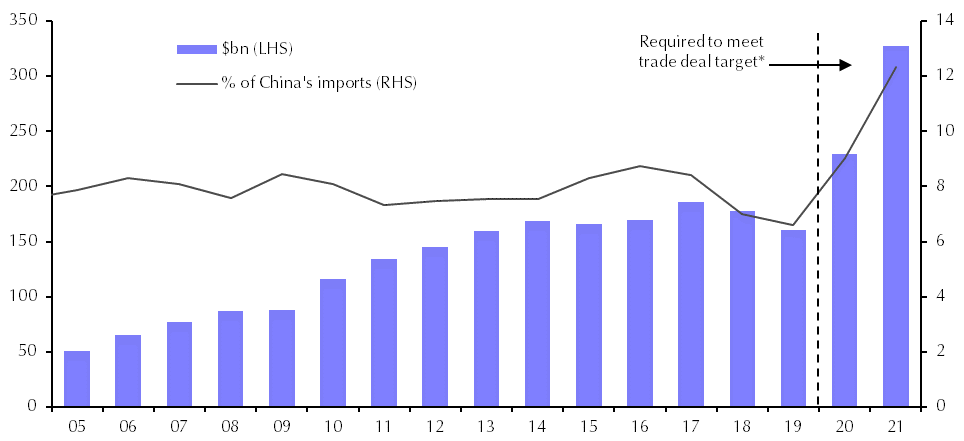

While there is scope for a rapid return to pre-trade war levels, this would only go half-way towards meeting the $200bn goal, which would require the US share of China’s imports to jump well above previous highs.

This seems unlikely to be achieved, not least because the US may not have the capacity to ramp up production of the goods that China needs on such a large scale.

Of the $200 billion, $40-50 billion should be of agricultural products, but the entire volume of China’s soybean and grain imports was little more than $40bn last year, and it cannot source all of its soybeans from the US given the timing of harvests. Moreover, China’s pigs, the main driver of its demand for soybeans, have been culled by nearly half in 2019 as a result of African Swine Fever.

To put that in perspective, U.S. farm exports to China have never topped $26 billion in any one year. China’s total agricultural imports in 2018 were $137 billion.

China’s imports of wheat and corn are tiny as the country is essentially self-sufficient, and they have huge stocks.

It seems that the US$40-50 billion figure was politically expedient rather than based on a detailed assessment of China’s demand or the ability of American farmers to expand output.

Additionally, since the trade war started last year China has increased its agricultural purchases from Brazil, Argentina and other countries. Beijing may have long term contracts it cannot break even if it intends to increase its purchases of US agricultural goods.

China has also said that future agricultural purchases will be dependent upon demand and market conditions rather than any target volume. China has reduced tariffs on 850 commodities from 1st January 2020 without any specific reference to the US.

Nevertheless, US farmers will be grateful for any increase in sales to China because they have borne the brunt of China’s retaliation to Trump’s tariffs.

As for non-agricultural products, it is hard to see which ones would contribute to a major increase in Chinese imports. Boeing cannot sell its bestselling 737 Max model until the various authorities clear it to fly, which looks unlikely to happen until well into 2020, and exports of high-tech electronics to China are being restricted by Congress.

Perhaps the area with the greatest potential is energy. The US Congress removed a ban on the export of oil and gas in December 2015 and exports have now reached nearly $90bn. China is the number one crude oil importer in the world after surpassing the United States in 2017 and is the number two natural gas importer according to the International Energy Administration.

However, China aims to enhance domestic energy security through increasing domestic exploration and reducing imports and its 13th Five Year Plan is filled with goals for self-sufficiency. However related reforms may open up new opportunities for private and foreign companies, and historically US companies have had a very weak presence in China’s oil and gas market.

Unfortunately the trade deal seems to fall well short of two key objectives.

First, the unrealistic goals for US exports to China risk causing disappointment and a return to tariff battles.

Second, there are no signs that the two sides are preparing to use this pause in the tariff dispute to reconsider the poor direction the bilateral relationship is taking towards decoupling and confrontation.

There are a few ways this could play out.

First, China could buy record amounts of U.S. agricultural and manufactured goods but fall well short of the targets. Trump may be satisfied, claiming success because historical records were reached.

Second, failure to reach the sales targets may not be enough for Trump, despite the record purchases, and he might then escalate the tariff dispute. That may lead Chinese officials to decide that further negotiations are pointless, leading to a trade war which damages both economies, although Beijing has far more resources to mitigate the impact.

Third, Washington may fudge the data to come closer to the sales target. For example, sales of goods produced in third countries with American intellectual property, such as semiconductors made in Singapore and Taiwan, might be included as U.S. exports.

Ultimately this cannot mark the end of tensions between the US and China, because it does not deal with the key issues which are global leadership in technology, access to the domestic Chinese market and geo-political hegemony. Let’s hope that they find ways to accommodate each other in these potentially destructive areas.

Sources:

https://global.matthewsasia.com/perspectives-on-asia/sinology/article-1678/default.fs

https://edition.cnn.com/2019/12/13/politics/us-china-trade-deal-explainer/index.html