In so doing we need to recognise the intergenerational unfairness of this situation. Millennials may at some distant point in the future be the beneficiaries of substantial inheritance, but until then they cannot afford what their parents enjoyed. They are faced with unaffordable housing, stagnation of productivity and earnings, and thin pension provision. Any solutions should be sensitive to this.

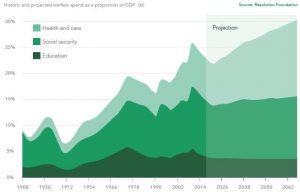

Moreover, while in 2016 there were 3.5 people of working age for every person of State pension age or older, that ratio will have fallen to 2.5 by 2036 (Source ONS). The UK has a “pay-as-you-go” system of welfare provision, which means that taxpayers, who are largely workers, fund it each year.

By way of context, the Resolution Foundation calculates that delivering the additional funding required by 2040 via income tax alone would be equivalent to almost doubling the basic rate of income tax, from 20p to 39p. Press Release 3rd January 2019

What follows is not all encompassing but shows a variety of ideas to consider. There are many more. I have set them out under a range of generic headings: reduce the size of the problem; improve the output of the economy; raise taxes; and share the burden with the corporate sector. There are no easy solutions, but I hope that everyone can find at least one idea which they believe has merit.

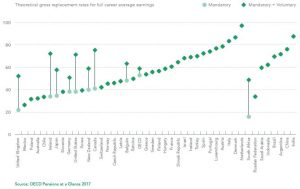

I think we should assume that the erosion of the inflation adjusted value of retirement and care budgets per person is unacceptable. The UK has nothing to be proud of. As the chart below shows the UK State pension is low relative to lifetime earnings when compared to other countries. The answer may lie in trying to delay the progress towards the 2.5 ratio mentioned above. There are two ways to do this.

Postpone the age at which people may receive their state pension.

Age UK states that, “From 2019, the state pension age will increase for both men and women to reach 66 by October 2020. The Government is planning further increases, which will raise the state pension age from 66 to 67 between 2026 and 2028.” Source: https://www.ageuk.org.uk/information-advice/money-legal/pensions/state-pension/changes-to-state-pension-age/

The age is now expected to rise to 68 by 2039 but should be raised sooner and further. The Government Actuary assumes state pension age will be 70 in the 2050s and 71 in the 2060s. This means anyone aged 21 to 30 will not get their state pension until they are 70. Those aged 20 or younger will have to wait until they are 71. (Source: https://www.rosaltmann.com/state-pension-age-risingto-70-even-though-uk-state-pension-is-lowest-in-the-world/)

We need more people in employment.

A large proportion of women work, the state pension age proposal above will keep people in work for longer, and we already know how many UK citizens will be entering the workforce in fifteen years’ time, because the births have happened. The obvious solution is to allow migrants to fill the gap. Not an easy solution! A more difficult one is to increase the quality of jobs.

When politicians and corporate leaders talk about improving productivity, they often mean cutting jobs, but we can see above that we need more people in employment rather than fewer. We also need to increase the value of what we do. Higher levels of education are essential but have a slow impact. Lower taxes on companies? We have done that. Become part of a larger economic bloc?

We have been there.

Apart from the next idea, the following cost nothing. And even the first may pay for itself.

How about writing off student debt?

There are various ways it could be done but the effect of diverting loan repayments to spending would have a positive impact. It would be akin to providing a tax cut and it would be focused upon relatively low earning workers. (Source GBIM)

Loan repayments are linked to future earnings, and many students are not expected to earn enough to fully repay the loans and interest before they are automatically written off, 30 years after graduation. 40-45 percent of current lending and the interest due on it is unlikely to be repaid, the government told a parliament committee last year. Reduce the liability for all students now and reduce tuition fees. Release their earnings into the economy!

The US Federal Reserve recently published (Consumer and Community Context, Jan 2019) two papers upon the effect of student loans upon the housing market and pointed to at least two effects. First, many borrowers fell behind on their student loans and damaged their credit, hurting their ability to qualify for mortgages. Second, many others have good credit but are unable or unwilling to save for a down payment on a home because they funnel a chunk of their disposable incomes toward student debt. UK and US loan practices are not identical, but the point is clear. Set the guardians of our future free! (Source: https://blog.ons.gov.uk/2018/12/17/accounting-for-student-loans-howwe-are-improving-the-recording-of-student-loans-in-government-accounts/)

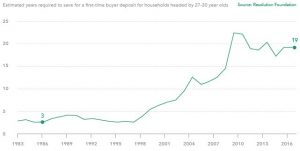

Boost the supply of new houses.

A perennial demand in British politics. Intergenerational equity demands that we now do something about it. We are short of housing and so it is too expensive.

If we spent a smaller part of our earnings on housing, we would have more for other things – like saving for a pension!

It is time for a policy shift towards the people who don’t have pensions and houses but do have debts and low earnings.

Provide tax incentives for household and small project investment in green energy.

This would increase turnover in the economy, increase power generation and reduce the costs of electricity thus stimulating the cutting of carbon emissions. Cutting the costs of electricity would improve company returns enabling higher investment and taxes.

Relax town planning regulations.

So many towns around the UK are rows of coffee shops, charity shops and chain stores. Many are depressing and people don’t like living there. We should reinvigorate our towns by making them good places to live and work. This would have multiple effects upon employment, transport and productivity. It would engage corporate and household investors and help decentralise the British economy.

Devolve policy making to local government.

Quite simply central government cannot deliver what local areas require. It is time to reverse the centralisation of power started by Margaret Thatcher and so enable local communities.

All the above would increase numbers of good jobs.

This should be the trickiest part, but two thirds of voters support it for investing in the NHS.

Simplify, reduce or remove some tax reliefs

Interested parties abound, but there is plenty of evidence to show that some of these reliefs do little to benefit the economy or society. Watch out for reductions in reliefs for: inheritance; entrepreneurs; Capital Gains Tax; and higher earners’ pension contributions. All of these benefit the “haves” and we are in a period of increased inequality.

Tax wealth more and income less

Wealth in Great Britain has grown significantly in recent decades while tax on it has remained completely flat. Since the 1980s wealth has surged from three to nearly seven times our GDP (or £13 trillion) (Source: Resolution Foundation). It is a bigger feature of modern Britain, relative to income, than anyone likes to admit.

Hypothecation

This means raising a tax for a specific purpose and ensuring that it is spent on that purpose. Simple, but may require a little courage to do it. The Treasury opposes this solution because it reduces

their overall control over fiscal policy. But the electorate need to know that if taxes are going up they are being spent in the way they have chosen.

Multi-nationals and tax evasion

Mentioned in every budget. Forget it. If it was easy, then successive governments would have been more successful in capturing it.

The introduction of the “living wage” and “workplace pensions” have been excellent steps in the right direction. Further increases are planned, and more should follow. Companies might also contemplate paying their employees more!

In reality we shall need to use a number of these ideas and others not mentioned here. Some will be more obviously palatable than others, but in the end the choices need to be made.