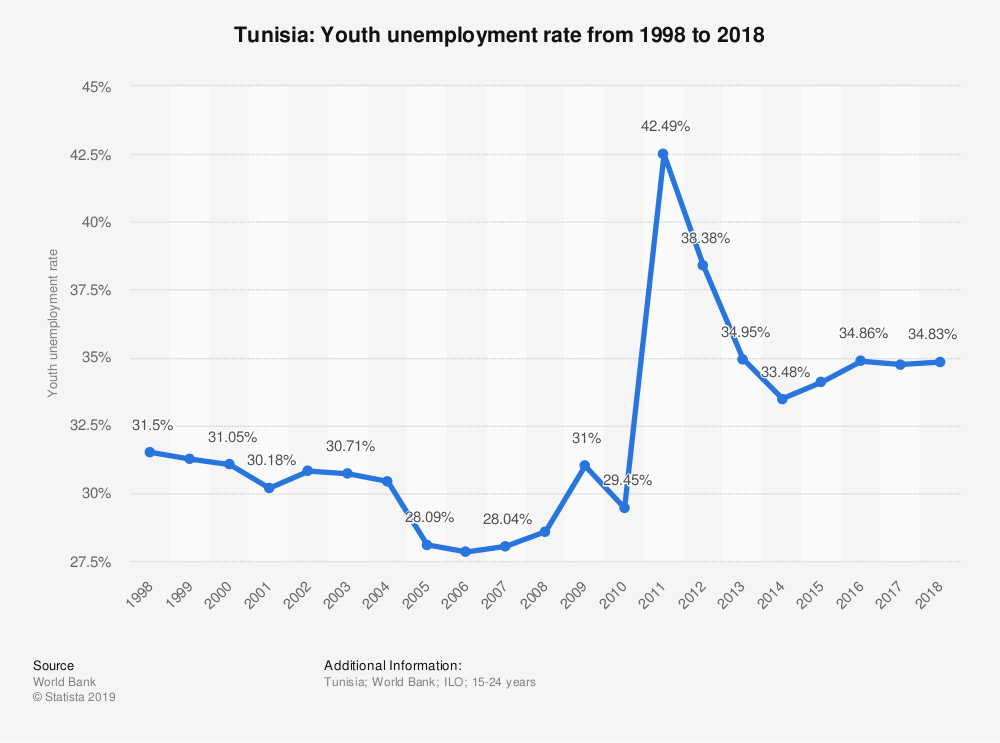

There has been a peaceful transition since then from the dictatorship of Ben Ali to pluralistic politics and the creation of a new constitution in 2014, but life for the average Tunisian citizen remains hard. Unemployment stands at over 15 percent, wages are stagnant, GDP is down, and debt is up. Tens of thousands of Tunisians have fled the country in search of better prospects. Youth unemployment is especially high.

On October 13th Tunisia held its second free presidential elections since the 2011 uprising. The election was held early following the death in July of President Beji Caid Essebsi while still in office. There was a landslide victory for “anti-establishment” candidate Kais Saied, a constitutional lawyer and retired professor. He won almost 73 percent of the vote and will now serve a five-year term as head of state.

There was nonetheless a sharp divide within the Tunisian electorate. Saied notably attracted university students, as well as educated middle-class people who do not benefit from the status quo. According to polls 86.1% of university-educated voters chose Saied while only 57.3% of those whose education ended after primary school did so. He also won over 90% of 18–25 year olds, while his opponent won over 50% of those over sixty. A clear generational divide has emerged as the younger generation hopes to break up the existing establishment.

Remarkably Saied built his campaign without the support of an established political party. This may however stymie his attempts to reinvigorate the economy, because the Parliamentary elections resulted in no overall control for any party. He will have to work hard to unite MPs behind his policies.

The former academic lawyer, who is also married to a judge, said that he could use the law to give people what they wanted, promising electoral reforms, including changes to local elections for regional representatives. There is a clear call today to protect the country from “corrupt elites”, but in the longer term the economy requires significant reform.

Jobs need to be created, whether this is in the agricultural sector or in technology, in towns or in the countryside. Greater regional security and stabilisation in tourism are needed and could encourage foreign investment. Improved legislation in many areas is required.

Tunisia needs help to modernise its competition, innovation, trade, and investment systems in ways that provide incentives for its local firms to become globally competitive and for foreign companies to invest in Tunisia, and so benefit more fully from the nearby large European market.

There is little scope to increase government spending. The average national budget deficit has exceeded 5.3% annually since 2012, and the total national debt has risen from 44.5% to 73.3% in that period.

Whether Tunisia will be able to escape a macroeconomic crisis remains unclear. The country may be obliged to learn how to live for the next few years on “the edge of chaos”, and to resist the maladies of entrenched cronyism and destructive populism.

Tunisia’s elections and their conduct are themselves a sign of its progress. This progress should be saluted. But the hard work of governing is just starting. Fiscal largesse remains years away.

Sources:

https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/10/tunisia-presidential-election-kais-saied-karoui

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/13/world/africa/tunisia-election-islamist.html

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-50087240

https://theforum.erf.org.eg/2019/05/07/unemployment-tunisia-high-among-women-youth/