At that time the US had laws on copyright, but they only applied to US citizens and not to foreigners. As a result, American publishers were distributing unauthorised copies of Dickens’ novels, which was understandably unacceptable to the author.

It is obvious that a novel is the clear product of a person’s imagination and ingenuity, and so clear whose intellectual property it is. Dickens’ claim was entirely reasonable. It takes a very long time to write a novel, and it is reasonable to be able to reap the rewards of such a commitment.

It is also likely that people would not spend time in researching or developing ideas if they can make no gain, pecuniary or otherwise, from doing so.

On the other hand, when it is protected by a patent or copyright, an idea becomes a monopoly, and monopolies may not be good things.

A balance needs to be found between protecting innovators and enabling the spread of good ideas.

Dickens would have been especially aware of the risks of not protecting his income. In 1823 his parents withdrew him from school because they could no longer afford the fees, and the following year, as a 12-year-old boy, he had to go to work in at Warren’s Blacking Factory in London, which made polish for boots. His father had been imprisoned in “The Marshalsea” for failing to repay a debt. Three of Dickens’ siblings and his mother had to live in the prison with his father. A traumatic experience for a small boy who had to live alone in a boarding house.

Scenes of poverty, indebtedness, prisons, factories and boarding houses abound throughout his novels. This personal childhood experience is reflected in Little Dorrit.

In David Copperfield, Mr Micawber made the oft-quoted comment, “Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure nineteen [pounds] nineteen [shillings] and six [pence], result happiness. Annual income twenty pounds, annual expenditure twenty pounds ought and six, result misery.”

The arcane nature of the law, and the impenetrable nature of the legal profession are also regular features of his stories.

When Dickens arrived in Boston, he was abundantly aware that the American economy was in its infancy, and that Americans wanted to use the best ideas which Europe had to offer – but to avoid paying for them! His ideas were being copied and he received nothing for them.

Since then the US has had a lot to say about intellectual property theft. It is the main issue hidden behind the current trade war with China. The Chinese had no copyright laws until 1991, but now they register more copyrights than any other nation.

But is protecting copyright always the best way forward?

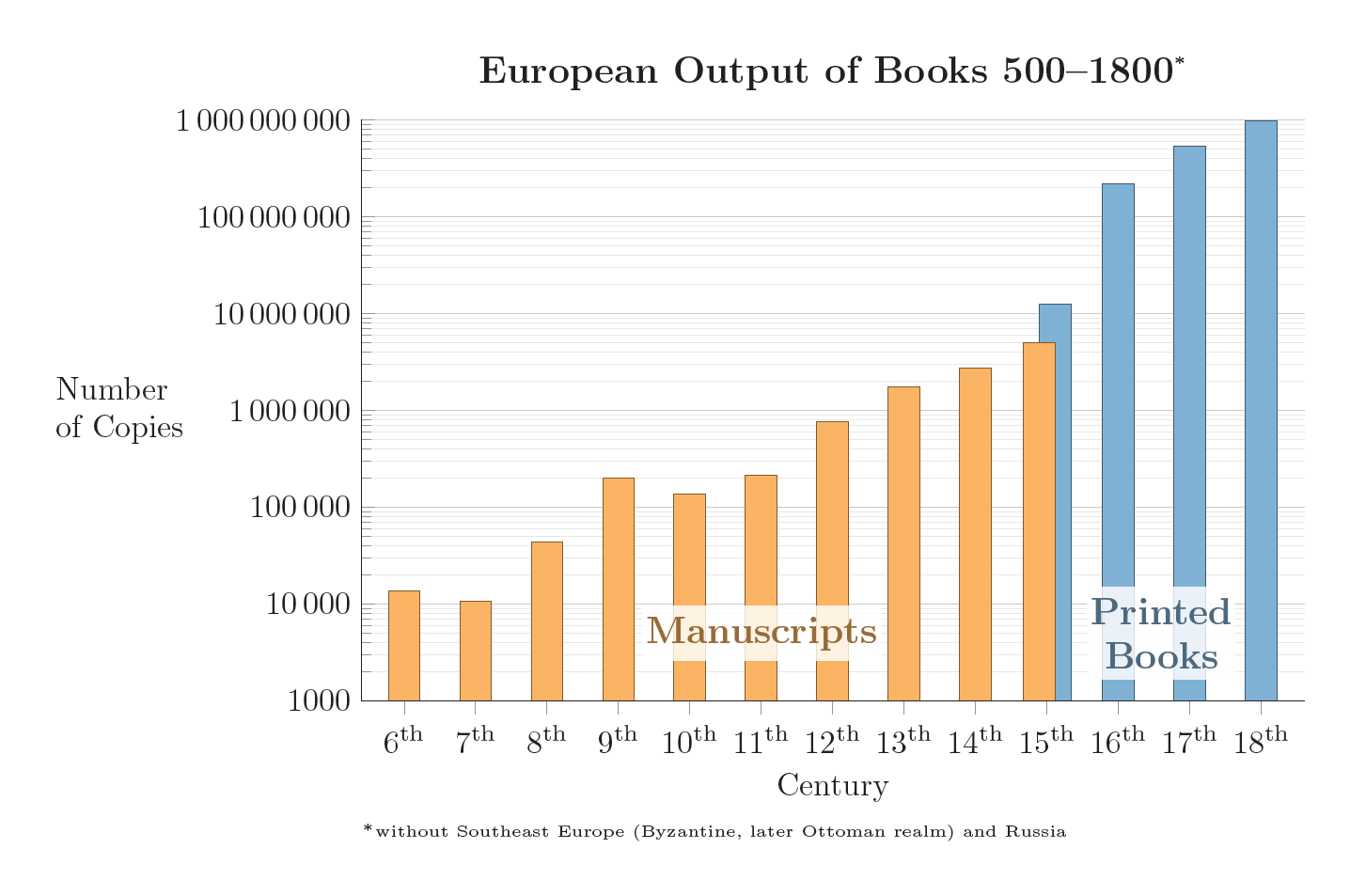

Copyright developed after the printing press came into use in Europe in the 1400s and 1500s. The printing press made it much cheaper to produce works but as there was initially no copyright law anyone could buy or rent a press and print any text. Popular new works were immediately re-published by competitors, so printers needed a constant stream of new material. Initial fees paid to authors for new works were high, and significantly supplemented the incomes of many academics. But they were also short-lived.

Printing brought significant social change across Europe. The rise in literacy led to a dramatic increase in demand for reading matter. Prices of reprints were low, so publications could be bought by poorer people, creating a mass audience.

In German-speaking areas, most publications were academic papers, and most were scientific and technical publications, often instruction manuals on topics such as dyke construction. After copyright law became established (in 1710 in England and Scotland, and in the 1840s in German-speaking areas) the low-price mass market vanished, and fewer, more expensive editions were published.

A famous example of the use of patents involved the steam engine. James Watt and his partner Matthew Boulton protected his ideas with patents, which allowed them to extract license fees from other users. It also enabled competitors to be thwarted, even when they developed better models.

But in 1800 the patents expired, and this unleashed many new products which had been repressed by Watt’s patents. Watt and Boulton however did not suffer. They stopped litigating, re-focused their attention upon innovation, and thrived.

Returning to the present day, copyright has expanded, and the expiry terms have been extended, often to 70 years after the death of the author. Trade deals have made them global in their effect.

Economists Michele Boldrin and David Levine argue that patents and copyrights have become controversial. They observe that teenagers are being sued for ‘pirating’ music and AIDS patients in Africa die due to their inability to pay for drugs that are high priced to satisfy patent holders. They question whether patents and copyrights are essential to thriving creation and innovation and conclude that they are not.

They argue that intellectual property is in fact an ‘intellectual monopoly’ that hinders rather than helps the free markets which have delivered wealth and innovation to our doorsteps. They conclude that the only sensible policy to follow is to eliminate the patents and copyright systems as they currently exist.

The experience of Watt and Boulton suggests they might be correct. First mover advantage, a good brand and the clear understanding of how and why an invention works may provide an adequate advantage.

This point of view is shared by Elon Musk who in 2014 opened his patent archive at Tesla to the wider industry in the belief that he too would benefit from the expansion of the electric car market.

But it is difficult to argue that such an approach should be universally applied. For example, the cost of discovery of new medicines is huge, and withdrawing the profit potential of new molecules which are protected by patent might be very counter-productive.

The arguments about the scope and duration of copyright will surely continue.

But what of Charles Dickens? He failed to get legal protection for his work, but years later the fame afforded him by all the fake copies of his works meant he was a celebrity in America. As a result, he made many millions of dollars as a public speaker.

Sources: https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/p0523g6y

https://www.shmoop.com/study-guides/biography/charles-dickens

David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

Copyright in Historical Perspective, p. 136-137, Patterson, 1968, Vanderbilt Univ. Press

Thadeusz, Frank (18 August 2010). “No Copyright Law: The Real Reason for Germany’s Industrial Expansion?”. Spiegel Online.

Lasar, Matthew (23 August 2010). “Did Weak Copyright Laws Help Germany Outpace The British Empire?”

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227390419_Against_Intellectual_Monopoly